I may be wrong, but I feel like ‘recycling’ used to be the face of sustainability. It was a simple concept to get behind and it made people feel good. Rather than reducing and reusing, which require a little more effort and thoughtfulness, recycling is like a guilt-free version of throwing something away i.e. to landfill. You can just toss something into a bin and it goes someplace more sustainable. Or does it?

“Only 9% makes it and the majority goes to landfill.“

Low Success Rate

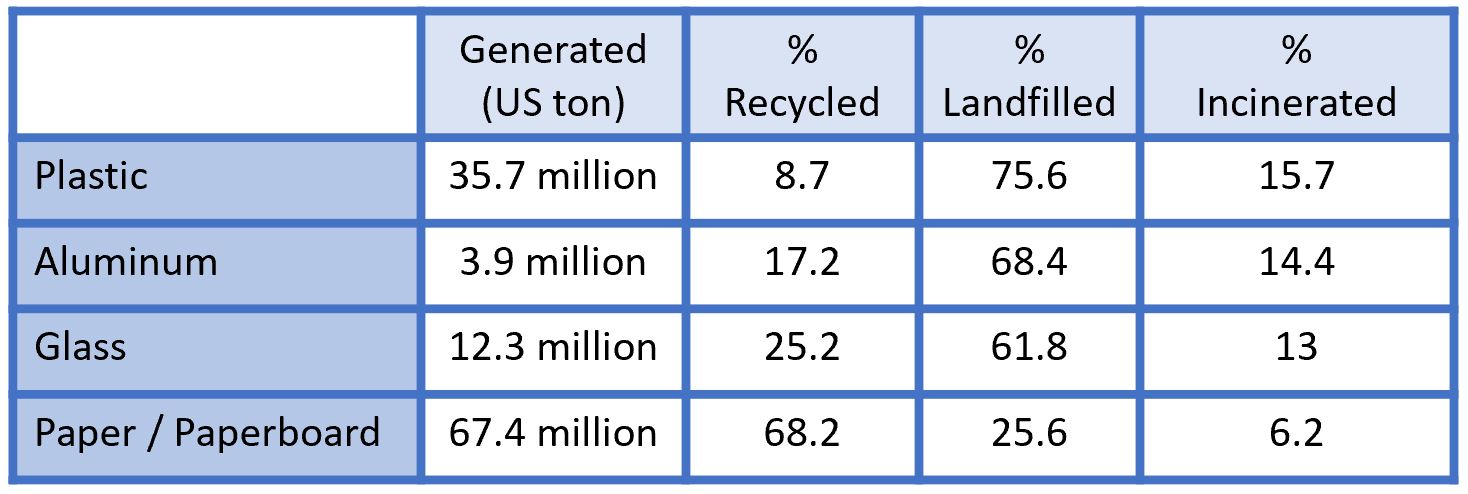

Much of the United States’ recyclable waste doesn’t actually get recycled. The information in the table below was gathered from a 2018 study on municipal solid waste done by the EPA1. As you can see, aside from paper, most of the waste that could be recycled just ends up in landfills.

So what’s the hold up? What’s getting in the way of our recycling success? Well, there are a number of reasons. Firstly, not everyone recycles. Some communities don’t have curbside pick-up programs. In those cases, one has to store their recyclables and regularly take them to a drop-off facility and to sort themselves. This is something I used to do at my old apartment, but not everyone has the time or will to do so. Some might not even have a drop-off facility nearby. What happens when you’re out in public and there are no recycling bins? When possible, I take my recyclables home with me to recycle them there, but again, not everyone would go to that much trouble. (Fun fact: Japanese cities have little to no public waste bins, so all trash, not just recyclables, must be discarded at home, so it’s not a completely unimaginable idea).

Contamination Leads to Landfill

For those who do recycle, are we doing it properly? There are so many protocols to follow. Make sure all food residue is rinsed out of containers, including anything that might be caked on. Plastic films, like shopping bags, sandwich bags, or packaging material, aren’t curbside recyclable and must be taken to specific drop-off locations, like grocery stores or retailers. Collecting all your recyclables into a large trash bag and then throwing that bag into the bin? Not a good practice, since sorting machines can’t handle that. Workers could manually take them out but that’s hard to guarantee. Shredded paper can only be recycled if it’s consolidated in a paper bag rather than being loose. Sort items into the correct bins, or if you have single-stream recycling, know which materials are accepted in that stream.

Matters can get more complicated as you get into specific local rules. Checking online or contacting your municipality is a good way to know what your local program accepts. But again, this level of necessary due diligence makes proper recycling a somewhat tedious practice to maintain.

Then there’s wishful recycling – when you don’t know for certain whether something is recyclable but recycle it anyway, in the hopes that it gets recycled. Wishfully-recycled (but not actually recyclable) items are commonly mixed material. Examples of these are milk cartons and paper cups (because of their plastic lining), soiled carboard or paper napkins, tea bags, toothpaste tubes or makeup items that are impossible to empty completely.

Take my recycling bin, as an example:

I had a spray bottle that had a plastic film label on it. Initially, I tossed it into the bin without giving it much thought. But as I was taking pictures for this post, I realized the label was not recyclable and I had to remove it first. How often do we missed small things like this when we recycle?

(And before you come for me for using plastic, need I remind you that everyone’s sustainability will look different? I’m still early in my journey and I reduce plastic waste in a number of other ways so relax.)

Improper recycling, along with not complying with the protocols mentioned above, can result in a contaminated batch. The resulting material needs to meet certain purity standards to be useful in the market, otherwise the whole batch will either get incinerated or sent to landfill. That means if one person works hard to sort and clean their recycling properly, but another person in the neighborhood along the same pick-up route, has contaminating material in theirs, the first person’s efforts are essentially negated. It’s not a perfect system, which is why there’s such a poor success rate.

Plastic is the Biggest Offender

From the table above, you can see that plastic is the hardest to recycle. Only 9% makes it and the majority goes to landfill. Only 9%! That’s wild, given the amount of effort we take to do better. Even when recycled, it’s still a nuisance. Unlike glass, metal, and paper, which can be recycled endlessly, plastic is downcycled, meaning the quality of the material degrades with each iteration. Eventually, even after being recycled a number of times, plastic will still end up in a landfill.

Additionally, plastic never actually breaks down. It just gets smaller and smaller… and smaller. This is why our environment, from our waters to our food, is riddled with microplastic pollution. It is estimated that we, on average, consume a credit card worth of plastic every week.

In other words, plastic is no friend to sustainability.

The Value of Recycled Material

For a long time, the US sent its recyclable waste to China for recycling, because China used it as a resource for manufacturing. But in 2016, the materials that the US sent over were 30% contaminated with non-recyclables, which ended up polluting China’s countryside and coastal shores. As a result, China would no longer accept material that didn’t meet stringent purity standards. Rather than cleaning up its own recycling practices, the US simply sold its waste to other countries. When those countries started implementing their own bans and regulations, the US looked to others still. A perfect example of the Global North passing on environmental problems to the Global South.

The fact was that the global market for recycled material had dissipated, which created problems domestically. The value of the end material was no longer justifying the means. Unable to sell their recycled materials, recycling facilities where unable to pay for operating costs and had to either reduce operations or shut down completely. At that point the economic issue trumps sustainability: why pay for recycling when disposing in landfill is cheaper? Which then leads to: why should I recycle when my city doesn’t even have a recycling program?

Finding the Incentive

After all the work and resources – both at the individual level and at the infrastructure level – is it worth it in the end? Maybe, maybe not.

Like I’ve said before, I have mixed emotions about recycling. The true goal should be to create less waste. Much much much less waste. If you were in a sinking ship, would it be better to figure out different ways of bailing out water or figure out ways to patch up the hole? We can do both, divert waste or reduce it. But one method allows the problem to persist while the other aims to eliminate the problem.

So how to we patch up the hole in recycling? Through education, legislation, and innovation. First, we educate each other on how to properly recycle (as I am doing with this post). Then, we talk to our government representatives to push forward policies that will ban certain levels of plastic or hold large companies accountable for their manufacturing and consumer waste. Lastly, we support creative and innovative ideas, like bio plastics, plastic alternatives, and effective take-back programs that make it easier for individuals to live more sustainably. Innovation can also come in the form of better recycling infrastructure and technology that would increase its viability and success.

I don’t think we should give up on recycling. Until we, as a society, can significantly reduce our waste, recycling is a necessary band-aid solution. However, since it is fraught with booby traps and inefficiencies, there are more impactful R’s of Sustainability that you can practice.

Reference

1United States Environmental Protection Agency – https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling